- Wealth Stack Weekly

- Posts

- Evergreen and Continuous Capital Funds

Evergreen and Continuous Capital Funds

The Structural Evolution of Private Markets Capital

Introduction: From Episodic Capital to Persistent Exposure

Private markets are undergoing a structural transformation that is best understood not as a cyclical product innovation, but as a fundamental change in how capital behaves over time. The closed-end drawdown model was engineered for a world in which institutional LPs could tolerate irregular cash flows, manage liquidity internally, and allocate capital through a sequence of discrete vintage commitments.

In contrast, the rise of evergreen and continuous capital vehicles reflects a different set of constraints: investors increasingly demand persistent exposure, reduced reinvestment friction, and a capital experience that more closely resembles that of public markets, albeit applied to illiquid assets.

At the same time, sponsors face economic incentives to stabilize fee revenue, reduce fundraising cyclicality, and extend asset management franchises beyond the finite horizon of traditional funds. The economic question is therefore not whether evergreen funds are “better” in isolation, but how continuous-capital mechanics reshape capital utilization, reinvestment risk, exposure stability, and the realized compounding path of returns.

This report evaluates that transformation through market adoption, performance evidence, structural design, and asset-class behavior, culminating in a capital-theory argument for why continuous capital represents a structurally superior way to compound private returns.

Market Adoption and Structural Scaling of Evergreen Capital

The growth trajectory of unlisted evergreen funds demonstrates that continuous capital is no longer a marginal construct within private markets. Aggregate net AUM rises from approximately $245 billion in 2022 to $302 billion in 2023, $412 billion in 2024, and nearly $493 billion by 2025. This $248 billion increase over three years implies a compound growth rate in the mid-20% range, which materially outpaces the growth of traditional closed-end fundraising in the same period.

What is especially revealing is not merely the scale of growth but its composition. Business Development Companies (BDCs) account for the largest share of expansion, increasing from $49 billion in 2022 to $167 billion in 2025, an absolute gain of $118 billion. Interval funds also expand meaningfully, from $59 billion to $126 billion, while tender offer vehicles rise from $43 billion to $102 billion. By contrast, non-traded REITs exhibit relative stability, moving from $94 billion to $99 billion over the period. This divergence suggests that the secular expansion of evergreen capital is being led less by traditional real estate wrappers and more by vehicles optimized for private credit, diversified private capital, and secondary strategies.

The structural implication is that “evergreen” is no longer a singular product category but a capital behavior implemented across multiple regulatory and liquidity frameworks. From a market-structure perspective, this diffusion is critical: it indicates that continuous capital is not dependent on the success of one fragile format but is being adopted across diverse channels, from retail-oriented interval funds to institutional-grade BDCs.

Product Proliferation and Institutionalization

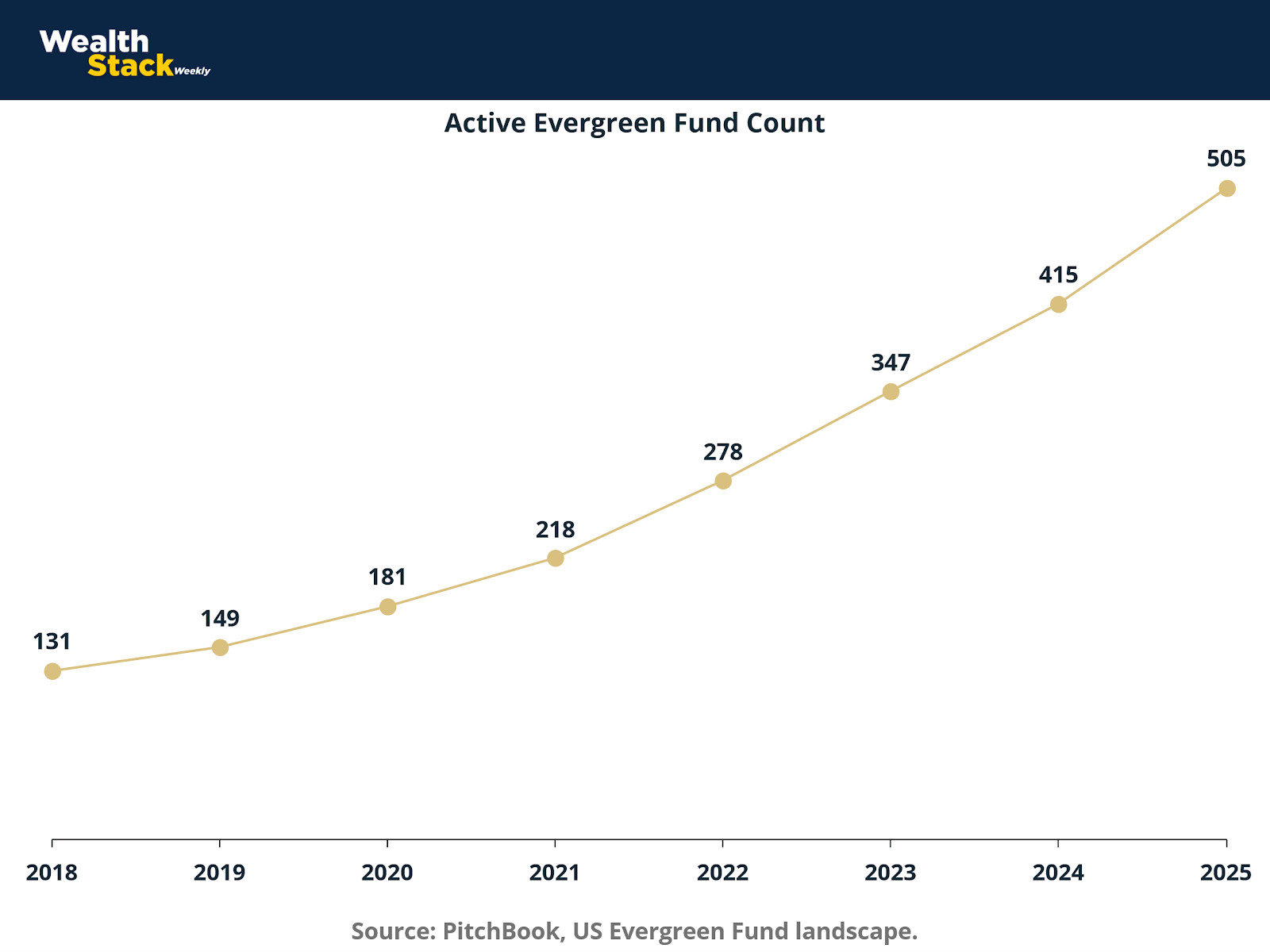

The rapid increase in the number of active evergreen funds reinforces that the growth in assets is matched by a growth in supply. The count expands from 131 vehicles in 2018 to over 500 by 2025. Notably, the inflection accelerates after 2021: the market adds roughly 60 vehicles from 2021 to 2022, nearly 70 from 2022 to 2023, another 68 from 2023 to 2024, and then more than 90 between 2024 and 2025.

This pace of proliferation has two important implications. First, evergreen funds are no longer experimental structures confined to early adopters; they are now being replicated across sponsors and administrators, signaling operational maturation in valuation systems, liquidity management, and reporting. Second, competition among evergreen products increasingly shifts away from structural novelty toward execution quality, particularly in portfolio construction, redemption design, and liquidity sleeves.

From an institutional perspective, the expansion in product count also reflects a broader shift in capital distribution. As private markets penetrate wealth platforms and semi-liquid channels, the classic closed-end commitment model becomes structurally misaligned with investor behavior. Evergreen vehicles reduce the temporal distance between investor intent and capital deployment, a feature that is increasingly essential in distribution-driven private capital.

Continuation Funds and the Logic of Extended Compounding

Continuation funds occupy a critical intermediate position in the evolution toward continuous capital. While not evergreen vehicles in the subscription/redemption sense, they operationalize the same economic principle: extending the compounding runway by decoupling asset life from fund life. The structure allows assets to be transferred from a legacy fund into a new continuation vehicle, financed by a mix of new LPs and rollover investors from the original fund.

Economically, continuation vehicles convert what would otherwise be a terminal liquidity event into an internalized reinvestment decision. They allow sponsors to avoid forced exits in suboptimal markets and give LPs the choice between liquidity and continued exposure. In doing so, continuation funds function as an endogenous liquidity valve for private markets, particularly when IPO and M&A markets are constrained.

However, the governance implications are non-trivial. Because the GP effectively sits on both sides of the transaction, pricing integrity, valuation independence, and conflict mitigation become first-order determinants of whether extended compounding benefits investors or merely entrenches sponsor economics. In the broader continuous-capital narrative, continuation funds demonstrate that the industry is actively constructing mechanisms to preserve compounding continuity even within closed-end legal frameworks.

Capital Behavior Across Fund Structures

This timeline graphic isolates the central economic friction continuous capital seeks to resolve: interruptions in compounding caused by idle capital and reinvestment gaps. Syndications, while efficient for single-asset exposure and high-conviction underwriting, impose episodic compounding at the investor level. Once a deal exits, capital becomes idle until redeployed, shifting reinvestment responsibility entirely to the investor.

Drawdown funds mitigate this by constructing diversified portfolios, but introduce a different discontinuity. Capital is committed upfront yet deployed gradually, and distributions return capital to the investor, reintroducing idle periods unless the LP actively manages pacing and liquidity. In effect, capital continuity becomes the investor’s operational burden.

Continuous capital funds invert this logic. They internalize reinvestment within the vehicle, minimizing stop-start behavior and allowing capital to remain persistently exposed to return-generating assets. In finance terms, this represents a shift from discrete investment projects toward a continuous exposure process with materially lower reinvestment timing risk. The structure does not eliminate risk; it reassigns it from capital-path risk to asset risk, which is more economically meaningful and manageable.

Compounding at the Portfolio Level

The table formalizes the locus of compounding across fund types. Drawdown funds compound at the deal level and externalize reinvestment decisions to LPs. Continuation funds extend compounding on selected assets under GP control for rollover investors. Evergreen funds compound at the portfolio level, with reinvestment managed centrally by the GP.

This distinction is fundamental because it separates asset-level dispersion from capital-path dispersion. Traditional performance analysis often conflates the two, attributing differences in outcomes to manager skill alone.

In reality, how consistently capital is exposed to assets is an independent driver of realized returns. When compounding occurs at the portfolio level, investor outcomes are less sensitive to the timing of exits and redeployments and more reflective of ongoing capital allocation policy. That policy can be superior or inferior, but at least it is centralized and engineered for continuity rather than emerging accidentally from the overlapping schedules of multiple funds.

Performance and Risk: Structural Evidence

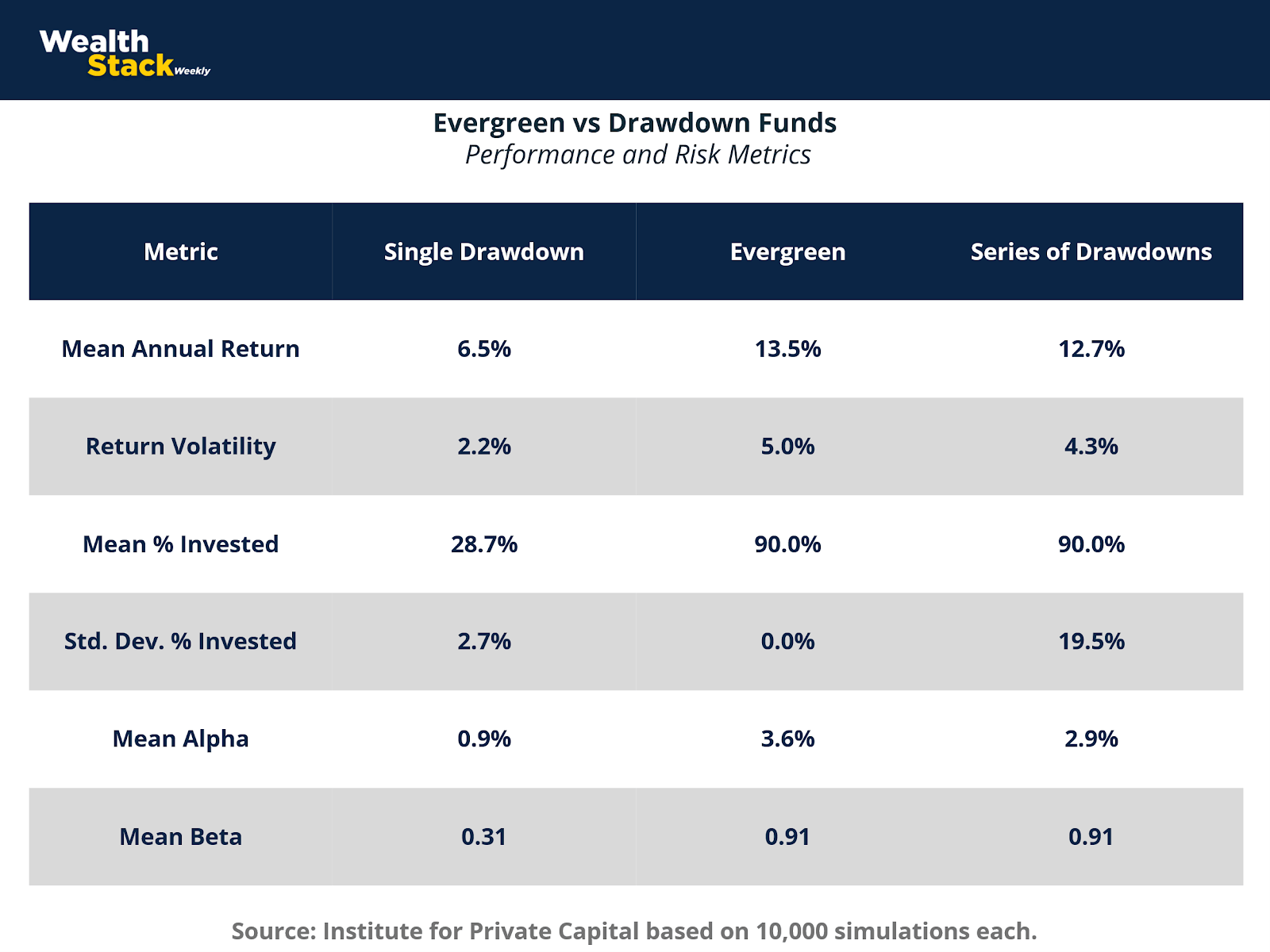

The simulation comparing an evergreen fund, a single drawdown fund, and a rolling series of drawdown funds provides the most direct evidence of structural impact. The single drawdown produces a mean annual return of 6.5%, largely because only 28.7% of capital is invested on average, with the remainder effectively sitting in cash. This is not an indictment of private assets, but of capital utilization.

Both the evergreen fund and the drawdown series maintain approximately 90% invested on average and share a mean beta of 0.91. Yet outcomes diverge: evergreen achieves a 13.5% mean annual return versus 12.7% for the drawdown series. The key difference lies in exposure stability. The evergreen fund exhibits zero standard deviation in the invested fraction by design, while the drawdown series shows nearly 20% volatility in percent invested. Even when average exposure is equal, time variation around that target introduces a compounding drag, which manifests in lower geometric returns. The higher estimated alpha for evergreen is therefore not a function of superior assets, but of superior capital continuity.

Return and Volatility Trade-Offs

The return and volatility comparison reinforces this interpretation. Evergreen’s mean return of 13.5% is more than double the single drawdown’s 6.5%, a seven-percentage-point gap driven almost entirely by differences in capital deployment. Volatility rises from 2.2% to 5.0%, but this increase is mechanically linked to being continuously exposed to private asset returns rather than intermittently parked in cash.

For allocators, this reframes the risk discussion. Evergreen funds appear “riskier” by volatility, yet they are economically more efficient in converting committed capital into invested capital and invested capital into compounded capital. In that sense, volatility becomes a reflection of engagement with the return engine rather than a deterioration in asset quality.

Asset-Class Behavior Inside Evergreen Vehicles

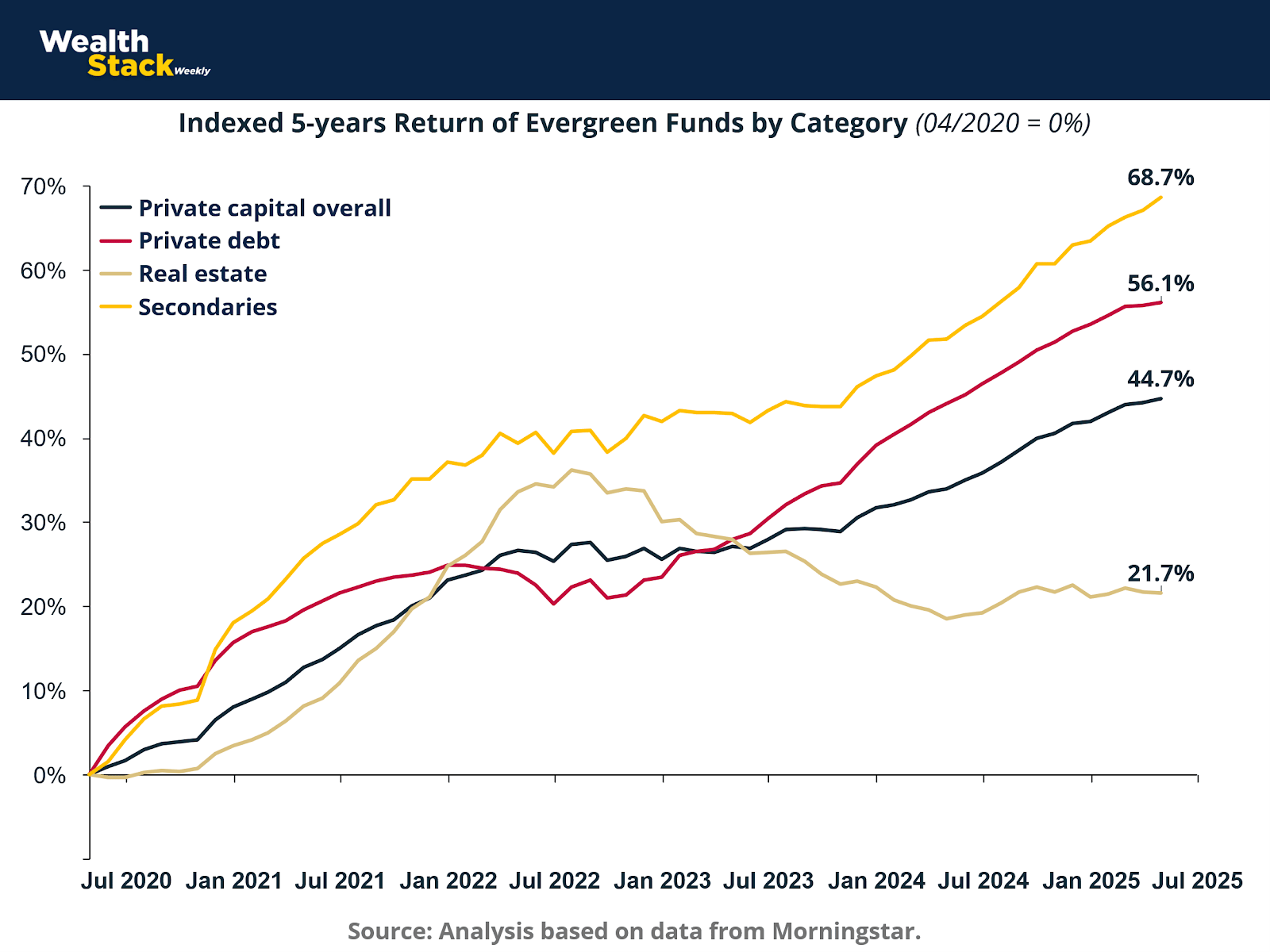

The dispersion in five-year indexed returns across evergreen funds demonstrates that evergreen is not an asset class but a wrapper applied to heterogeneous strategies. Nonetheless, patterns are visible. Private debt and secondaries tend to show smoother, more consistently upward trajectories than more cyclically sensitive segments such as real estate. This reflects differences in cash-flow predictability, deployment velocity, and sensitivity to exit markets.

The implication is that evergreen structures are most coherent where reinvestment is structurally feasible and where missed time translates directly into lost economic return, as in credit.

In equity strategies where exits are binary and deployment capacity is constrained, the benefits of continuous capital are more conditional on manager discipline and opportunity flow.

Category-Level Performance and Feasibility

At the category level, secondaries lead with approximately 68.7% cumulative growth over the period, followed by private debt at 56.1%, private capital overall at 44.7%, and real estate at 21.7%. This ranking is economically intuitive in a post-2020 environment characterized by higher rates, constrained exits, and elevated dispersion in asset quality.

For evergreen structures, these outcomes serve as feasibility signals. Strategies with higher reinvestment efficiency and more predictable cash generation are structurally better suited to designs that promise periodic liquidity and continuous compounding.

The data suggests that evergreen’s success has been anchored in categories where wrapper mechanics and asset cash-flow profiles are naturally aligned.

Volatility, Valuation, and Risk Interpretation

The volatility data adds nuance to the risk narrative. Volatility varies materially by category and by year, reflecting both economic conditions and valuation practices. In 2021, real estate volatility peaks near 6.5%, while in 2022 volatility compresses across all categories, likely reflecting valuation smoothing during a period of market stress. By 2024, dispersion reappears, with secondaries and private debt showing higher volatility than real estate.

The key takeaway is that evergreen volatility should not be interpreted mechanically. NAV-based reporting dampens high-frequency movements, meaning that apparent stability may mask underlying economic risk. Therefore, evergreen risk must be evaluated alongside liquidity terms, valuation governance, and stress behavior, rather than as a simple function of reported volatility.

Conclusion — Continuous Capital and the Economics of Keeping Compounding Turned On

Traditional performance metrics such as IRR implicitly assume capital is already working. They are silent on what happens before deployment and after distributions, when capital often sits idle or earns materially lower returns. The charts in this report make that blind spot visible. A single drawdown fund delivers a 6.5% mean return because only 28.7% of capital is invested on average, while evergreen maintains 90% investment with a stable exposure path and therefore achieves a 13.5% mean return under identical asset assumptions.

Even when a drawdown series is engineered to reach 90% invested on average, instability in the invested fraction introduces a compounding drag, resulting in lower geometric returns. This is the core economic case for continuous capital. It does not create alpha by itself; it preserves the conditions under which alpha can compound by minimizing idle time and reinvestment friction.

In environments where deployment capacity is strong and governance is robust, continuous capital structures represent a rational evolution of private markets. They transform private investing from episodic exposure into persistent exposure and shift the allocator’s problem from managing cash-flow timing to evaluating manager skill, portfolio construction, and liquidity design. In that sense, continuous capital is not merely a product category; it is a structural answer to how private returns can compound efficiently in an illiquid world.

Sources & References

CFA Institute. (2021). Permanent Capital: The Holy Grail of Private Markets. https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2021/06/01/permanent-capital-the-holy-grail-of-private-markets/

EQT. (2025). The Rise of Continuation Funds in Private Equity. https://eqtgroup.com/thinq/private-markets/continuation-funds-private-equity

Moonfare. (2025). Continuation fund. https://www.moonfare.com/glossary/continuation-fund

Morningstar. https://www.morningstar.com/company

PitchBook. (2025). US Evergreen Fund Landscape. https://pitchbook.com/news/reports/q4-2025-us-evergreen-fund-landscape

SG Analytics. (2025). Evergreen Funds in 2025: Growth, Gaps, and the Case for Caution. https://www.sganalytics.com/blog/evergreen-funds-growth-gaps-and-caution/

White Case. (2022). Continuation funds emerge as attractive options for PE fund managers and investors. https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/managing-volatility-considerations-taiwan-continuation-funds-emerge-attractive-options-pe