- Wealth Stack Weekly

- Posts

- Why Real Estate, Not Gold, Is the Superior Inflation Hedge

Why Real Estate, Not Gold, Is the Superior Inflation Hedge

This structural dominance is not anecdotal—it is mathematical.

1) Inflation

Inflation in the real economy is neither abstract nor evenly distributed. It concentrates first and most persistently in necessities—housing, food, utilities, and services—before dissipating through discretionary categories. December 2025’s CPI data underscores this reality. Headline inflation remained at 2.7% year over year, unchanged from November, but this stability masks ongoing pressure in consumer staples. Food prices, both at home and away from home, rose 0.7% month over month. Utility gas prices increased 4.4% in a single month and over 11% year over year. These are not volatile, speculative categories; they are structural components of household budgets.

More importantly, inflation remains elevated where it matters most for persistence: shelter. Even as economists point to disinflationary trends and expect inflation to ease in the second half of 2026, shelter inflation continues to run above the headline rate. This reflects the slow-resetting nature of rents and housing services. Unlike goods prices, which can fall quickly due to discounts, inventory gluts, or margin compression, housing prices and rents reprice infrequently and asymmetrically. Once they move higher, they tend to stay there.

This structural dominance is not anecdotal—it is mathematical. Housing is the single largest component of CPI, accounting for over 40% of the total basket. As a result, inflation is not merely influenced by housing costs; it is largely driven by them. Any serious discussion of inflation hedging must therefore begin with housing, not commodities or financial abstractions.

Shelter’s ongoing contribution to inflation is visible in the most recent CPI breakdown. In December 2025, shelter prices rose 0.4% month over month and 3.2% year over year, outpacing both headline CPI and core goods inflation. Even as energy commodities declined and apparel inflation remained muted, shelter continued to exert upward pressure. This is why inflation often feels more persistent to households than headline numbers suggest: rent is slow to rise, but even slower to fall.

2) Real Estate

Real estate operates inside the inflation system rather than reacting to it from the outside. Housing costs are not just correlated with inflation; they are embedded in its measurement and lived experience. Over long horizons, this positioning allows real estate to reprice steadily as wages, construction costs, and replacement values rise.

The long-term behavior of housing prices illustrates this clearly. Over the past decade, U.S. house prices increased by approximately 101%, far exceeding cumulative inflation over the same period. This appreciation occurred across multiple economic regimes, including periods of low inflation, tightening monetary policy, and post-pandemic price normalization. Housing prices respond not to inflation panic, but to structural supply constraints and nominal income growth.

Income-producing real estate extends this dynamic beyond asset prices into cash flow. Public real estate, as captured by the FTSE Nareit U.S. Real Estate Index, has compounded significantly since the early 1970s. This compounding reflects not only appreciation, but the continuous reinvestment of rental income across inflationary and disinflationary cycles. Real estate does not require inflation to spike to function; it benefits from inflation when it occurs and continues to operate when it does not.

Crucially, this performance has been delivered with volatility that is moderate relative to long-term returns. Since 1971, real estate generated roughly 9% annualized returns with volatility around 15–16%. Over the last decade, volatility declined materially even as returns remained positive. This stability is not accidental. Rental income smooths returns, while fixed-rate, long-duration debt allows inflation to erode liabilities over time, enhancing real equity value.

3) Gold

Gold occupies a fundamentally different position in the inflation narrative. It is not embedded in the inflation system; it reacts to perceptions of monetary instability. Over centuries, gold has preserved value episodically, but it has not compounded consistently. Its major repricing events have coincided with regime shifts rather than gradual inflationary processes.

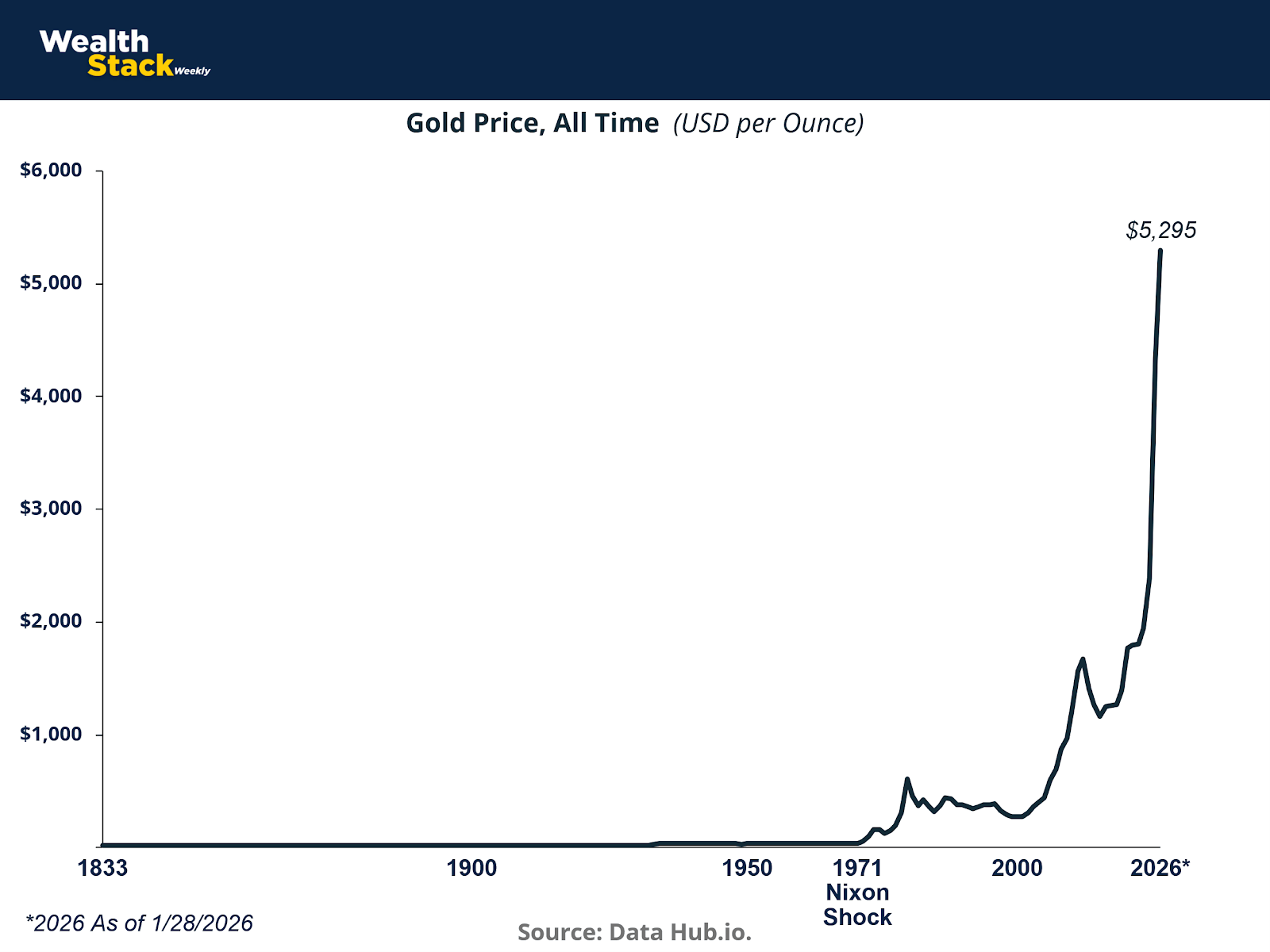

This pattern is evident in gold’s long-term price history. For extended periods, gold prices remained relatively flat in real terms, punctuated by sharp increases following the collapse of the gold standard in 1971 and during subsequent crises. Gold’s value responds less to realized inflation than to expectations about monetary credibility and future instability.

Gold’s return profile further highlights this limitation. While gold has delivered strong returns over specific windows—particularly in the last decade—its long-term compounded returns are materially lower than those of income-producing assets.

At the same time, gold’s volatility remains persistently high. Even during periods of strong performance, gold exposes investors to large drawdowns and long stretches of stagnation.

Gold’s defining characteristic as an inflation hedge is that it produces no cash flow. It does not reprice rents, service debt, or generate income that can be reinvested while inflation is occurring. To access its value, an investor must sell it at the prevailing market price.

In the case of physical gold, this comes with additional frictions: storage costs, insurance, custody fees, and, in many cases, reliance on bank or vault infrastructure that is neither free nor liquid.

4) Real Estate vs Gold

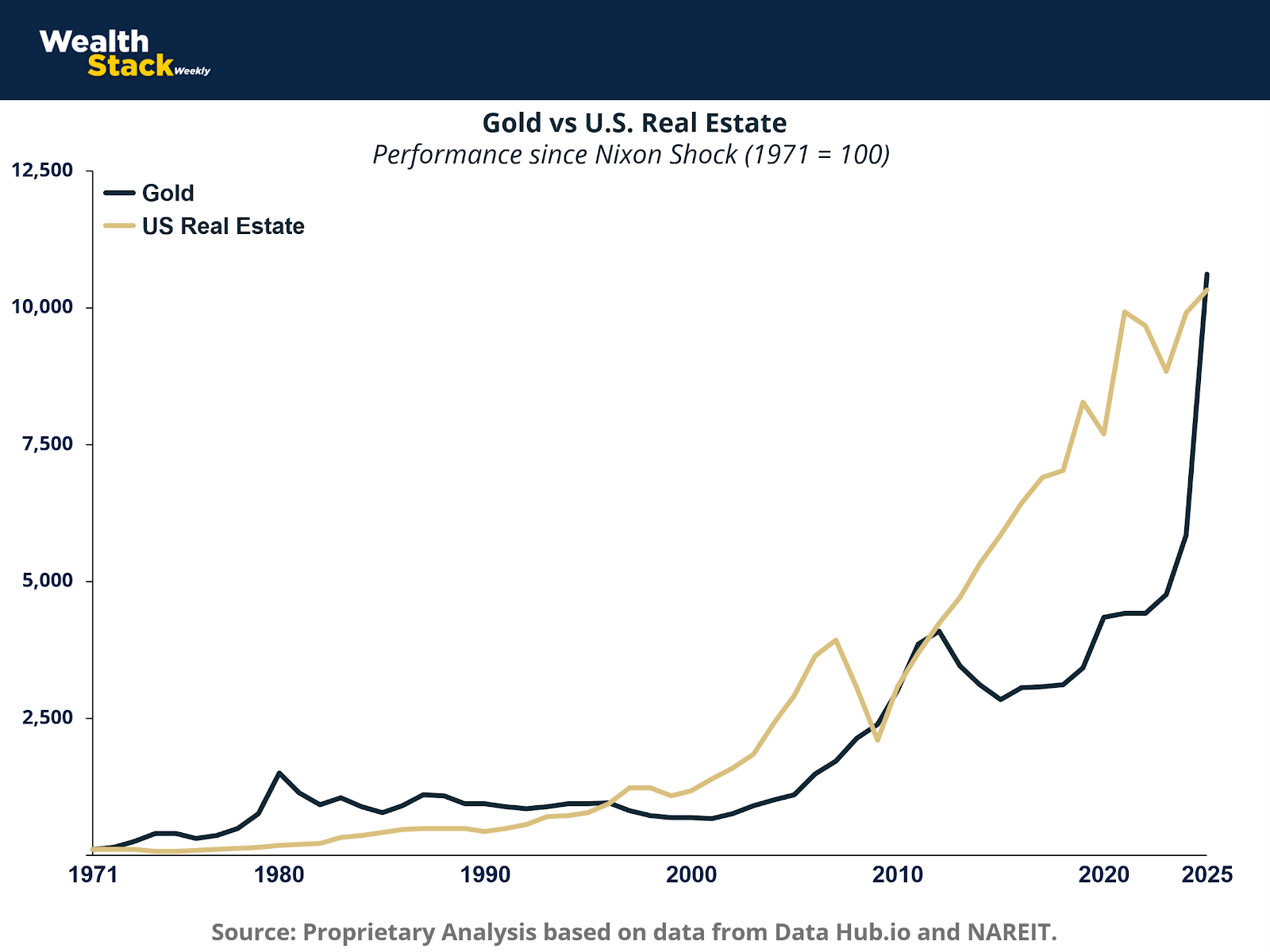

The divergence between real estate and gold becomes most apparent when viewed side by side over long horizons. Since the Nixon Shock, both assets have benefited from a fiat monetary regime, but they have done so in fundamentally different ways. Real estate’s performance has been cumulative and compounding, while gold’s has been episodic and sentiment-driven.

When inflation is explicitly introduced into the comparison, the distinction sharpens further. Real estate has not only outpaced inflation, but has done so by generating income throughout the inflationary period. Gold, while preserving value in nominal terms, has lagged real estate materially and offered no internal compounding mechanism.

Risk-adjusted outcomes reinforce this conclusion. Across multiple periods—from globalization to the 21st century to the last decade—real estate consistently delivers higher returns per unit of volatility than gold. Gold’s higher volatility reflects its dependence on macro narratives and investor psychology. Real estate’s superior risk-adjusted profile reflects contractual cash flows, embedded pricing power, and balance-sheet asymmetry created by fixed-rate debt.

When returns are noized by volatility, real estate’s advantage persists. Over long horizons, real estate converts inflation into both income and equity growth more efficiently than gold converts uncertainty into price appreciation.

5) Conclusion

Real estate is a superior hedge against inflation not simply because it has outperformed gold historically—even including the most recent gold bull run—but because it operates differently at a structural level. Real estate does not just appreciate alongside inflation; it absorbs inflation through rent, reprices steadily over time, and generates cash flow while inflation is occurring. That cash flow compounds. It can be reinvested, used to service fixed-rate debt, or deployed into new opportunities without liquidating the underlying asset.

Gold, by contrast, only appreciates. It produces no income and no internal compounding. To access its value, the investor must sell it. In the case of physical gold, this process is further burdened by storage, insurance, and custody costs—often through Swiss vaults or banking systems that are neither inexpensive nor frictionless. Gold can serve as insurance against extreme monetary disorder, but insurance is not a system, and it is not a compounding strategy.

Inflation is not a single event reminder—it is a long-duration cash-flow phenomenon. Assets that live inside that system, reprice with it, and pay investors while it unfolds are structurally advantaged. Gold watches inflation. Real estate works through it—and pays you along the way.

Sources & References

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2026). CONSUMER PRICE INDEX – DECEMBER 2025. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cpi.pdf

CNBC. (2026). Here’s the inflation breakdown for December 2025 — in one chart. https://www.cnbc.com/2026/01/13/cpi-inflation-december-2025-breakdown.html

DataHub.io. (2026). Gold Prices. https://datahub.io/core/gold-prices

GoldPrice.com. (2026). Gold Price History. https://goldprice.org/gold-price-history.html

NAREIT. Monthly Index Values & Returns. https://www.reit.com/data-research/reit-indexes/monthly-index-values-returns

Statista. (2025). The Components of the Consumer Price Index. https://www.statista.com/chart/31266/composition-of-the-consumer-price-index/?srsltid=AfmBOooHT6B0_OYOl7YzJ7nxdsdRA98IheDRB_bnffsvXqbkJnyeGPhC

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average [CPIAUCSL], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL, January 29, 2026.

U.S. Federal Housing. (2026). FHFA House Price Index Datasets. https://www.fhfa.gov/data/hpi/datasets

Premium Perks

Since you are an Wealth Stack Subscriber, you get access to all the full length reports our research team makes every week. Interested in learning all the hard data behind the article? If so, this report is just for you.

|

Want to check the other reports? Visit our website.